I could still hear his sobs. Standing by the bed, his posture slightly bent like a fishing hook. He pulled the cloth from her face, his shoulders trembling, arms visibly shaking through his black sleeveless t-shirt. He leaned in to fish for a breath, or maybe a heartbeat. Touched her face, held her hand, and then placed it gently on her chest.

Was her body still warm when he held her? I wondered. It was when I held her wrist to feel a pulse. She could have been his mother, or grandmother. Regardless, she meant something to him. I felt an itch, to reach out and tell him it’s going to be okay, however long it would take. But it wasn’t my place. I, after all, am the sonographer on whose examination bed she died. “A darenLithinin”, I remembered somebody saying.

Grief had already arrived uninvited on Sunday evening when I received the news of my grandmother’s passing. I tried and failed multiple times to pass a yellow thread through the small eye of a needle as my tears kept spilling like springs from a waterfall. Each tear was a betrayal. I couldn’t control the one thing I could still hold on to, my composure. My hands trembled with every attempt to push through the weight of the loss of my ailing grandmother. I tried to deal with that grief how I knew best: Denial.

And then Thursday morning I found myself crying alone in an open field as I tried to put into words the grief of losing a father, a grandfather, and now a grandmother. Nothing at that moment had warned me that later I’d witness the demise of somebody’s parent, wife, sister, neighbour, friend. It’s a different experience learning someone had died, and watching the life leave out of them. To be in the same room with death. To know that it’s there, so close, but it’s not you it’s come for.

Being in the same room as the body seemed almost natural. Years of strolling past cadavers on the way to class in medical school could desensitize you to the sight of dead bodies. But this wasn’t a nameless cadaver on a dissecting table in a lab. Her name was Nana Iliya, and half an hour before, she’d been brought into my examination room to be scanned. Half an hour before, she could be called out to. Now her name was said in hushes and whispers. In all my years of grieving, its understanding eludes me, but death is even ridiculous; how you can have a person alive one moment and un-alive the next. How it was possible to put your arms around death, stare it in the face, and still live.

Hearing him sob quietly in the reception, I thought about my grandmother, Dada. I wondered who was with her in the hospital when she drew her last breath. Who noticed first when her chest stopped heaving, syncopate with her breath? At that moment, my empathy leapt out of the cold sterile examination room, defied the loud hum of the standing fan in the reception and whispered, “it’s okay, you’re going to be okay”. I had no tears left to cry, and I couldn’t muster the right words to soothe his aching heart. But vicariously, I lived through his grief.

The loss of my grandmother stung even hard given the circumstance in which she had left us, left me. I saw her last Christmas, spoke on the phone with her a week before she passed. We had unfinished business, she and I.

Last Christmas was the first time in twelve years since I’d last seen my grandmother. For as long as I can remember, I never felt a pull to visit. Especially after my father and grandfather died, there was no obligation in my heart to return. My grandfather would often be offended if we went to visit him without first stopping at my grandmother’s. Despite their separation, he always acknowledged the fact that she was the mother of his son—our father, and therefore deserved that respect. But me? I never longed to step foot in that house, not because I didn’t love her. God, I loved her almost as much as I had loved my grandfather. But I stayed away because of him…

My step-grandfather. The man who made those years some of the most harrowing of my life. I could still hear the disdain in his voice when he looked at me in the eyes years ago and said to me, “kai ne arnen da ba ka son sallah ko?”. That moment was the point of no return for me, the threshold where my soul had made its decision: I would never allow him to affect me again. That was around 2009, years after I had left that house and only visited occasionally on holidays.

When we visited last Christmas, the house was nothing like I had remembered. Old structures have been erased and replaced with new ones; the single flats now duplexed. I was taking it all in, silently processing, when my brother’s voice broke through the fragile silence.

“Do you remember this truck?”

His words hit me like a sudden unprovoked punch, I felt a violent thud in my chest. A jolt of panic surged through me, and I wanted to recoil. Why had he asked, forcing that memory to the surface when I had done everything to bury it?

Of course, I remember the truck. It was impossible not to. But acknowledging it meant acknowledging everything that came with it: The events, the feelings. I quickly dismissed it as if it were insignificant, as if the years of avoidance had not just crumbled under my brother’s innocent question.

But I’ve always carried my memories with me, more like a burden than a blessing. The smallest, seemingly inconsequential details of events etch themselves in my mind and resurface uninvited. I rarely forget. I only bury, hoping the weight will lessen with time.

Growing up in that house was like living under a constant shadow. Every Friday my step-grandfather would force my brothers and me into the back of that mini pickup truck, drag us to the mosque, and demand we pray. Every morning he’d wake us for Fajr prayers. And some nights we’d be torn from sleep and made to memorize verses from the Quran. Never minding that we were Christians and have always been so. There was no warmth in his eyes, just cold entitlement. A dictator disguised as a caretaker.

When I finally freed myself from the shackles of his control, those memories were the first thing I buried. I didn’t want them. I didn’t want him. And I most certainly didn’t want any part of that house ever again. So, when he looked at me, years later, and spoke those words—so casually, so dismissively, it was as though I was transported back to that exact moment, and I swore, I’d never return.

But that house, no matter how much I wish to distance myself from it, had always been a part of me. My grandmother lived there, along with my step-uncles and other branches I’d severed myself from. Like my uncle Osama, my step-grandmother’s son, who’s about the same age as my younger brother. The last time I saw him, he was a little child, running around the compound, naked and carefree, as children often did. Now, he’s grown, his face framed by maturity. And then there’s my step-grandmothers, three remarkable women, each of whom I adore as much as I adored my grandmother. My favourite of the three was Osama’s mother. She has a wide diastema that graces her face when her lips are drawn in a smile.

My bloodline is irreversibly linked to that place, no matter how much it tore me apart.

I promised my grandmother I’d be back next Christmas, and now, I’d never be able to live up to the promise. I never truly said goodbye to my grandmother. There were things I wished I said, like my reasons for staying away all those years, and now, I never will. That is perhaps the hardest part: to know that that time is gone, along with any chance of closure.

Looking at the young man, I couldn’t help but wonder how much we had in common. What was his relationship with the woman who had passed? What made her loss sting more for him than anyone else in the room? At that moment, and in that way, our griefs intersected. Even if we’ll never share the same answers, I realize that like him, my pain is still unfinished.

***

1. “A darenLithinin”: (Hausa) on a Thursday night

2. “kai ne arnen da ba ka son sallah ko?”: (Hausa) you’re the heathen who doesn’t like to pray, right?

3. Fajr prayer: the first of the five obligatory Muslim prayers.

4. “it was possible to put your arms around death, stare it in the face, and still live”: a direct quote from author, Umar Turaki’s novel, Such A Beautiful Thing To Behold.

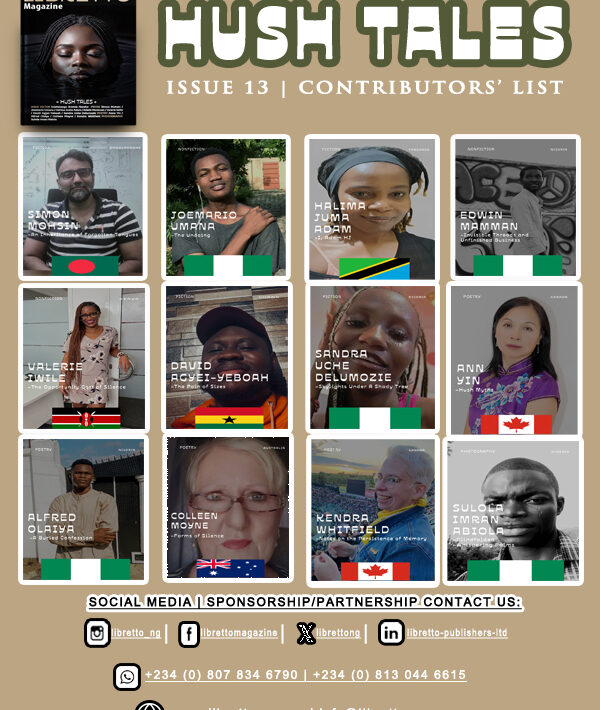

EDWIN MAMMAN is a sonographer and writer from Kaduna, Nigeria. He has works published on KAFART’s The Revue, Fiery Scribe Review, CON-SCIO, African Writers Space, Magpies Magazine, and forthcoming elsewhere. He enjoys movies and music when he is not working and writing, and he loves to take long walks in nature. He tweets @edwinmamman, and can be reached via email on edvinmamman@gmail.com